As Jerry Lee Lewis sang on his 1957 release, catalogue no, Sun 267. Saturday morning dawned dreary and overcast. I thought the South was supposed to be hot by the middle of May but I’m still waiting for that to happen.

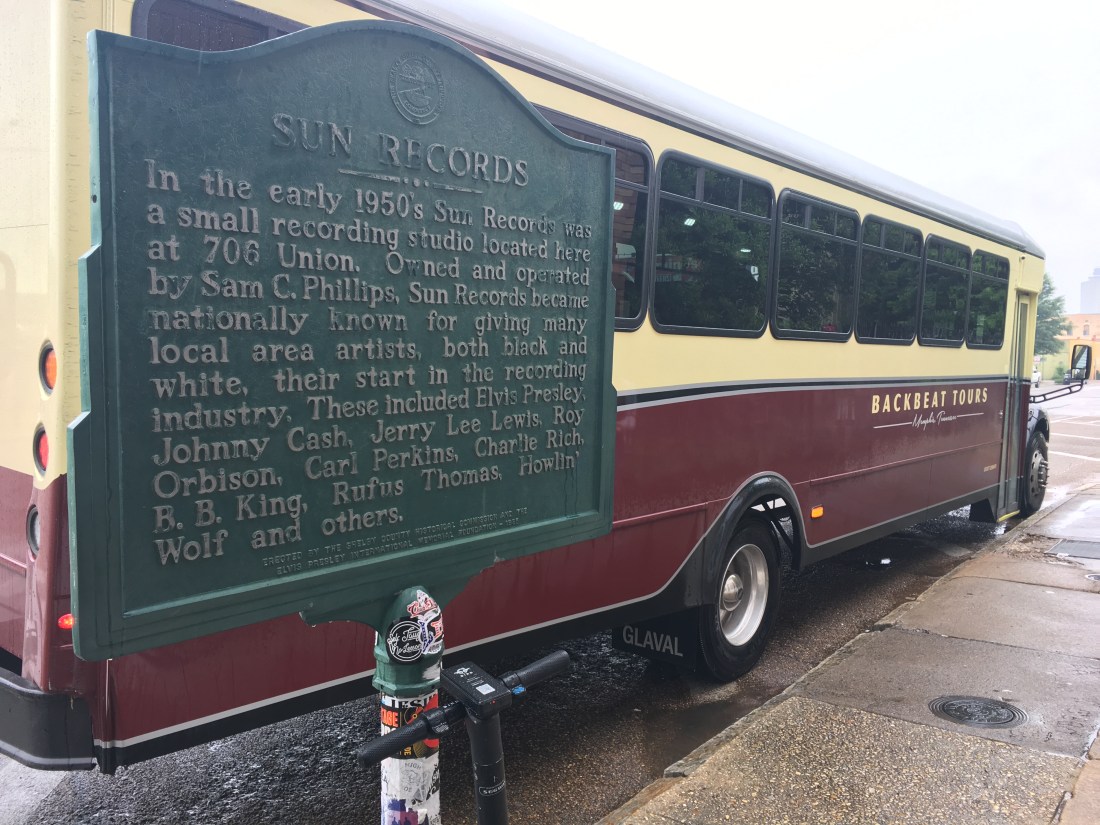

The big musical pilgrimage not yet completed here in Memphis was a visit to Sun Studios. Today we would put that right. It was here, in a nondescript brick building at 706 Union Avenue, that rock and roll music was born.

Sam Phillips opened the Memphis Recording Service in January 1950, and from day 1, struggled to keep the business afloat. To make ends meet, he would record anything and everything: speeches, weddings, funerals, literally anything. In June of that year he launched his own label, called Phillips Records, which folded after one failed release.

He did, however, continue with his quest to find the sound he was looking for – a sound that would take the blues music he loved and somehow change it for a mass appeal – and specifically white – audience. Without his own label, he partnered with Chess Records in Chicago and sent them recordings for release.

When Ike Turner (of Clarksdale, Mississippi) rolled into Memphis in March 1951 for a recording session with his Kings of Rhythm, Sam was there to capture it. The only problem was that the band’s guitar amp had fallen off the back of the car on the drive from Clarksdale. They had stopped to recover it but when they set up in the studio, they discovered that the speaker was cracked. There was no money for a replacement, so they did their best to repair the damage by stuffing newspaper into the gap. And then they recorded Rocket 88, widely acknowledged as the first rock and roll record, notable for its distinctive, fuzzy guitar sound, thanks to that damaged amp. Ike Turner was hugely upset to discover that, for reasons unknown, the recording that was released by Chess Records was credited to Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats. Brenston was, in fact, the sax player in Ike’s band and another Clarksdale native.

Sam was encouraged to have another try at running a label as well as a studio and, in 1952, started Sun Records. In the label’s first year, he recorded BB King, Rufus Thomas, and Howlin’ Wolf but the label still struggled to make money. When, in July 1954, he agreed to record a young unknown by the name of Elvis Presley, he was hoping for great things from his distinctive voice. Elvis, together with musicians Scotty Moore and Bill Black, recorded ballads and gospel songs all through the session. This was not what Sam wanted to hear. As he was giving up on the session, Elvis picked up a guitar and started playing an obscure blues tune by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup that he had heard as a kid. That tune was That’s All Right released as Sun 209. On the B-Side was a Bill Monroe song, Blue Moon of Kentucky, although Elvis recorded it in 4/4 time as opposed to Bill’s waltz version. Bill later joked that he made more money from Elvis’ B-Side than any of his own recordings and subsequently started performing the song in 3/4 time at the start and changing to 4/4 halfway through. But with this single release, this little Memphis building changed the course of popular music. Enthusiastic youngsters beat a path to the door of Sun. The careers of Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, Carl Perkins were all launched from here.

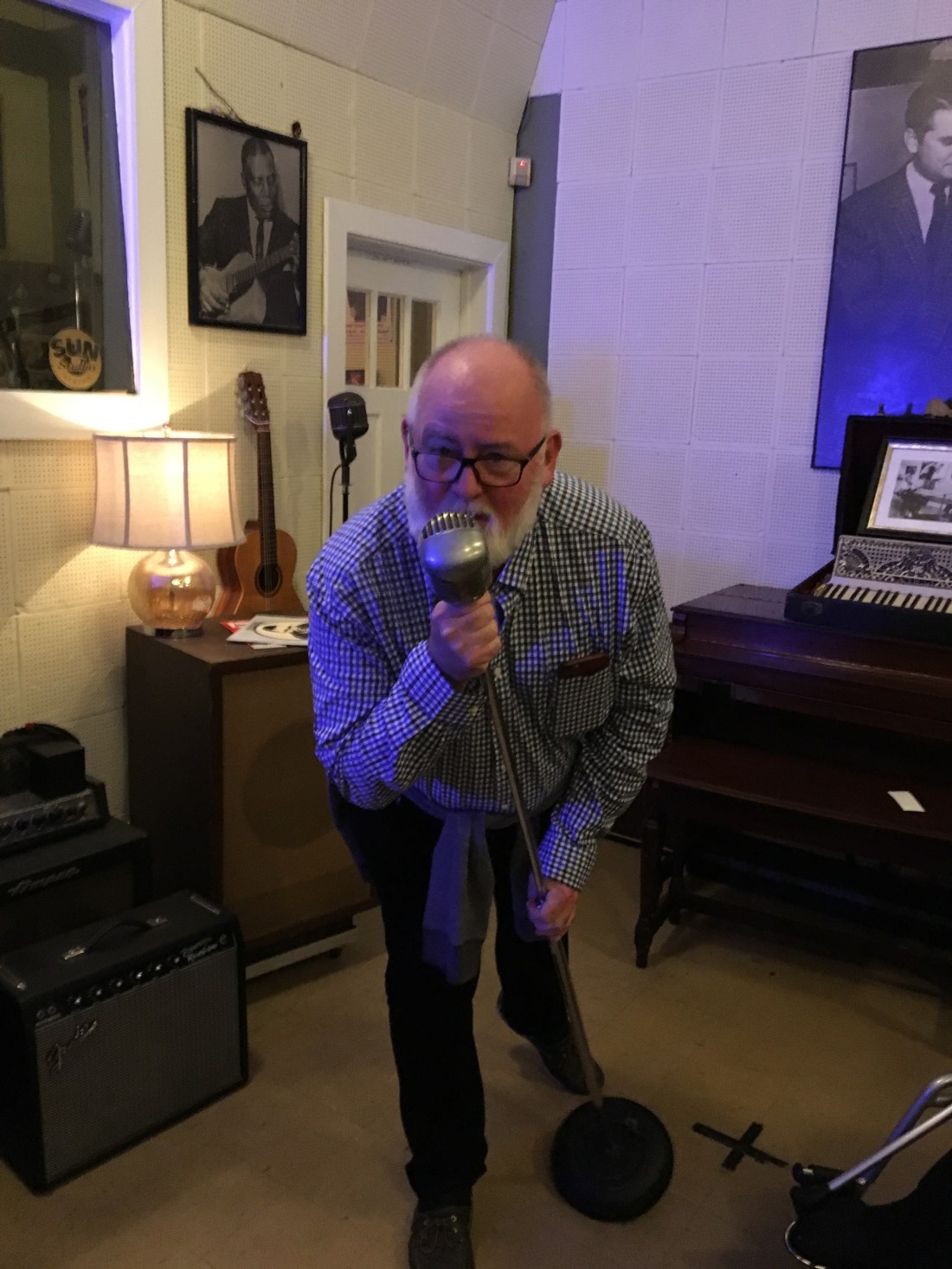

And that’s why we simply had to visit here. Unlike the Stax Museum, much of the studio is original and the setup is largely the same as it was back in the fifties when these guys were laying down musical milestones. There are even genuine vintage microphones there.

Striking the pose was simply irresistible to me. You can still book sessions to record at Sun Studios. The tour around the building was excellent. The guides and staff there are all working musicians and they have some great stories to tell.

After finishing here, we had a considerably more sombre stop to make on our sightseeing trip.

On 4 April 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated as he stood on the balcony of Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Downtown Memphis. The motel is now the National Civil Rights Museum and that was our next port of call.

The place is obviously popular, since there wasn’t a single space left in the car park when we got there. There was plenty of on-street parking, so we loaded the meter for three hours and went inside. This is an incredible place. The exhibits are set up really well, charting the history of human rights in the USA chronologically which, almost by definition, means the history of black human rights. From the drive to preserve the slave trade as an engine of economic growth, to the Civil War. From the rights acquired by freed slaves in the Reconstruction period, to the implementation of Jim Crow laws and the effective disenfranchisement of a huge percentage of Southern African Americans.

The implementation of a culture of non-violent protest to achieve change in the law created tensions all across America in the fifties and sixties. This was not just a Southern problem, which is how I always simplistically viewed it from my foreign viewpoint. Rosa Parks is one of the most famous icons of peaceful protest but there were so many people who sacrificed so much to make progress.

I also hadn’t realised the extent to which the television coverage of how these peaceful protests were being broken up by Southern law enforcement officers was being utilised as a tool of Cold War propaganda by the Soviets. It was this Soviet agitation, and wider international condemnation, that was at least partly responsible for forcing the hands of JFK and, later, LBJ to enact civil rights legislation in the face of extreme opposition.

If you find yourself in Memphis, you owe it to yourself to visit this place.